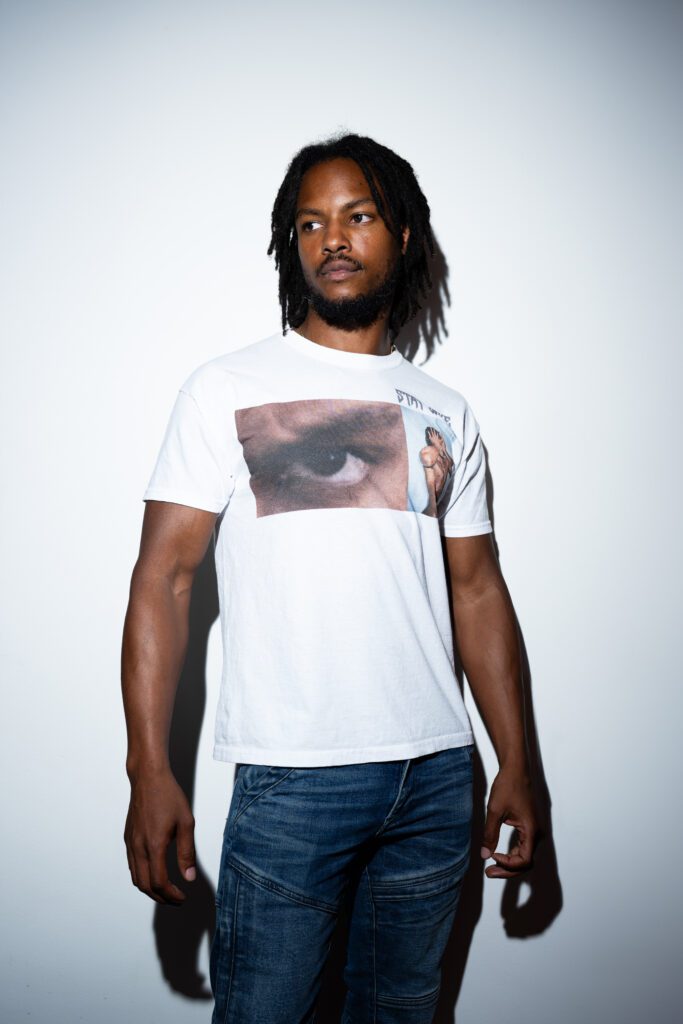

Who are you, and what do you love most about what you do?

My name is JeanPaul Paula – that’s who I am. What I love the most is that I get to connect with a lot of different people, and I think, at least I hope, that I invite them into dreaming and thinking bigger.

Which role does sustainability play within your work and practice?

In a way, it would be the awareness that I try to share on the Black experience. I guess it’s sustainable for Black to be woke or aware of themselves and know that they’re not alone. I think that gradually it allows people to think about sustainability in the bigger picture because I don’t think that sustainability only means being green and acting green. To me, it’s about creating space, having dialogue and hopefully gradually rewriting our history books so that they can be more realistic in terms of Black people’s identity and our definition of self.

The exhibition at Fashion for Good is called Knowing Cotton Otherwise. Unlike some of the other installations within this exhibition, you did a pop-up show. Can you tell us more about this and what your process was like?

I think it’s a very big subject that is being watered down because of people’s feelings and the connection to reality. How do you invite Black people to discuss something on such a graphic subject and then deal with it in quite a light way because we’re talking about it in the West. There’s no sense for us to discuss cotton because we are the problem. So in trying to find a way to express myself within this concept, I deeply went into questions such as: What is cotton? Where does it come from? How does it connect to us as people of colour? And everything I found was obviously horrible and something that I was already aware of, and I really had a hard time trying to find my place in how I could discuss that.

I actually had a few months to think about it because of how it went with the museum. I’m just saying all of this because I think people should know. I feel like dialogue with an institution sometimes makes it hard for artists to express themselves especially when they’re not ready internally to have dialogue. After that, I went quite easy actually. After figuring out that I really wanted to do something out of self-expression, I went into the idea of how I presented my art over the years and if I could do something that would feed into that. That’s where I got into finding the end result as well. I was quite comfortable saying this is enough that I have to show and didn’t feel like I needed to dive deeper than that.

That’s when I decided to make a bed with prints of myself on it. Essentially my body and my skin, in that sense stands for us as Black people who are interwoven with cotton. How big it is couldn’t have been possible without the transatlantic slave trade, and especially the people that were enslaved in the timeline cotton really became big. It is almost impossible for us to touch cotton that is clean, so I tried to go into how I can explain to people that this fabric we use is slavery and that it defines it as well. I tried to find a way to connect cotton to awareness. I compared it to states of sleep. There are five states of sleeping, but I focused on four, and those states of sleeping have a lot to do with your consciousness and where you are in terms of if you are awake or not. I wanted to wake people up. As I discussed wokeness, it became very connected to the idea of being awake and asleep, and where do you do that? In bed.

In my work, I’ve reintroduced myself in my family’s photo album after being kicked out for being gay. In most of my exhibitions, I built a part of our house. In 2020 when I was broke, I had to go home, and I wrote my first concept of something that changed my life, which turned out to be the Clavin Klein exhibition I did a few years back. Being home and having conversations with them made me want to reintroduce my Black gay self into my family. And this is what most of my work has been about, home settings where I use the surroundings as a photo album. I show myself and my family, and how we coexist, especially being Black people. This is why I decided to make the bed. I wanted it to be like my bedroom.

You chose to title your pop-up exhibition “WOKE | In Bed with JeanPaul Paula”. I think some of us cringe hearing the term since it has been misused and overused a lot. What made you choose this subject and title?

That was my intention. I didn’t want people to feel too invited to come, and I wanted them to cringe because it was gonna be quite cringeworthy. I think that this whole subject is quite cringe as well, and I wanted all of us to understand that we are not necessarily aware of what we put on our bodies, especially Black people and the connection to that. In a way, I did choose this to be a little bit derogatory, and I did want people to be a bit uncomfortable. I completely understand what you mean, especially when I look at what has been done with it in white Media. It has completely been taken out of context, and I wanted to remind people that it’s not a weapon. I’m not pointing my finger at other Black people saying “Hey you’re not here, and you’re not aware enough.” I’m just saying that within the conversation of awareness, I use this word because it’s our Black version of not just saying be prepared for what the white world has to give you, but be aware of it as well, like be knowledgeable.

What did you hope for people to take away after seeing your work in the museum, and how did you feel afterwards?

I don’t think that people got to take away what I wanted because when you do an open conversation like this it becomes less about me and more about them. I think that every individual person took from it what they took. Unfortunately the moment I started talking to the white person in the space, that became the main focus. As much as I tried to derive from it, even after, it became almost impossible for that energy to leave the space, which is probably why in the future I might just say no white people at all, which is something that I didn’t want to do because I feel like in this country that conversation isn’t held like that. It’s impossible for us to have a conversation on our own and actually shift or change anything.

Why is a community-driven mindset that strives for collectivity important to you?

Super important, but at the same time, I think it has a specific time for individuals, which I think is very normal if you’re new somewhere, or a student. I think it’s normal to have the idea that if you’re actually making friends that think the same, you can move together. I love that, but I don’t think my generation really had that luxury as much as people have it now, which cost me to be very much an individual that gets to do things on their own.

In what way do you relate this to the generation?

I feel like in my generation there weren’t a lot of people of colour around who did specifically what I did, so collectivity with them was almost impossible. Also in fashion, which is where I started, unfortunately in Holland, there’s an atmosphere which is not very inviting to people. So I had to create my own being within that. I do have my own personal way of working with collectivity, and I do still believe that it’s hyper important for the community to do that. I think it’s almost impossible to move at all actually if you do it on your own. So I have my friends, and I have my safe spaces, but in terms of being collective, I feel like I draw more to the side of trying to make space and then helping people physically or actively with what they could do. Like am I collective with my family, or do I just have a family? I invite them very much so they are part of what I do. My parents helped build up this exhibition and all of the other ones that I’ve done except for one I did in Paris. If there’s a budget, I include my people first and people that I trust.